I recently read Lost in Transition: The Dark Side of Emerging Adulthood by Christian Smith.

The in-depth interviews that sociologist Smith and his collaborators did with 230 young adults paint a disturbing picture of the results of hyper individualism, consumerism and moral relativism. The book focuses on five areas: confused moral reasoning, routine intoxication, materialistic life goals, regrettable sexual experiences, and disengagement from civic and political life.

It caught me up short.

I thought, “Here I am providing a solution to bounded group religiosity and many of my students have been absorbing society’s emphasis on tolerance as supreme virtue their whole lives. Their problem is not a bounded approach; they think like a fuzzy group.”

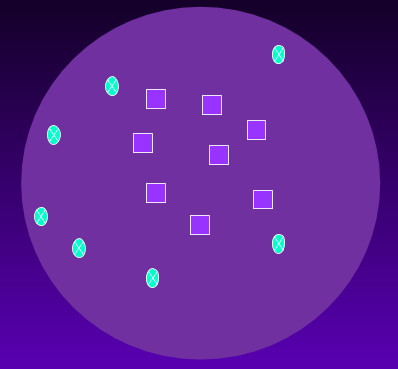

A bounded group creates a list of essential characteristics that determine whether a person belongs to that group or not. The group has a clear boundary line.

A fuzzy group has no clear sense of demands or expectations. In one sense a fuzzy group is the total opposite of a bounded group – one has very clear sense of in and out, the other is very unclear. With time there may be no distinction between those who belong and those who do not.

Although Paul Hiebert (from whom I borrowed these ideas) included descriptions of all three approaches-- bounded, fuzzy and centered--I had only taught and written about bounded and centered. Bounded, not fuzzy, was the problem I had encountered in churches, and centered was the solution. Reading Smith left me unsure of that approach.

I considered totally retooling, continuing to use material on bounded groups in contexts like Honduras or Ethiopia, but not in Fresno. Yet, almost immediately I thought of students who, like thirsty plants, drank up my teaching on Galatians and related it directly to current or recent experiences in churches of bounded character. Clearly there is still a need to proclaim freedom from bounded group religiosity in the North American context.

So, I did retool, but it was not by talking about fuzzy groups rather than bounded. Starting in this spring I presented all three approaches--bounded, fuzzy, and centered--in the same class. I invite you to watch a video of that lecture.

My thesis is that a centered approach, as seen in Jesus and Paul, is a corrective to both bounded churches and to the “whateverism” and tolerance as supreme virtue of a fuzzy approach. In the next blog I will share some ideas on how to help people move from a fuzzy approach to a centered approach. That was the reason I started talking about fuzzy groups in class--to work at a corrective. But something interesting happened. Including an explanation of fuzzy groups aided students understanding of the centered approach.

After including fuzzy ethics in class this year, I have observed three key improvements:

Centered– Now more clearly a different paradigm

I have always stated that the centered approach, the way of Jesus, is a radically different paradigm than a bounded approach. Students appeared to grasp that more easily this year. By presenting a fuzzy approach as re-working of a bounded group, giving it a very fuzzy boundary line, I can describe a continuum from radically bounded to radically fuzzy. All on that continuum are of the same paradigm. The centered approach is fundamentally different. It is not on the continuum, it is a different paradigm.

Centered—Now more clearly not “Christianity-lite”

Over the years the biggest challenge I have had in explaining a centered approach has been helping people understand it is not relativistic. In contrast to the bounded approach they perceive it as too loose. I think I have gotten much better at showing it is not “Christianity-lite” (listen to all the ways I try to do that in the current version of the class), but still some students did not seem to get it—until this year! Adding the fuzzy group to the mix enabled students to see and have a name for a relativistic version, and see the centered approach as something different. Students this year more easily saw that the centered approach includes a call to changed living flowing from a relationship with Jesus because they contrasted the centered approach not only with bounded, but also with fuzzy.

Centered--Now more clearly making ethical demands beyond tolerance.

This greater clarity lessened the pushback by those who had argued against the centered approach from one direction, but the same clarity brought pushback from the other direction. Some students who are more attracted to a fuzzy approach now critiqued the centered approach for having too strong of an ethical call. In the past they probably would have interpreted the centered approach in a fuzzier way because I presented it as the alternative to bounded, and they knew bounded was problematic. For them as well it was clear that the centered approach is different than the fuzzy approach. It does ask more of people than to just practice tolerance as supreme virtue.

Our culture continues to frame ethical dilemmas somewhere on this continuum between out-grouping boundedness and all inclusive fuzziness, leaning more and more toward the relative virtues of tolerance and personal authenticity. When you are wrestling with an ethical problem, I encourage you to recenter on Jesus--not to exclude but to discover a new way of being.

How does the centered approach reframe something for you more clearly around Jesus?

What is an example of how you have found talking about or utilizing a centered approach helpful?

What other potential benefits do you see from adding a description of a fuzzy group to the discussion about bounded and centered?